I’ve been thinking for a while about starting a series of posts focused on areas I struggle with – because researching and writing about them forces me to understand them better. So here goes the first one: page numbering – or, more accurately, pagination.

I. Where it all began: leaves and pages

In traditional book design, everything starts with the concept of a leaf. A leaf is a single sheet of paper in a book, and it has two sides: the recto (front) and the verso (back). This means that one leaf equals two pages. Let’s take a simple example. Imagine an A4 format photobook that contains only one sheet of paper – that’s one leaf, which gives us two pages: the recto and the verso. If the book has 20 leaves, it will contain 40 pages (20 recto + 20 verso).

Additional reading:

https://www.biblio.com/book_collecting_terminology/leaves-61

https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parts_of_a_book

https://princetonlibrary.org/book-anatomy/

The first known printed book to include foliation – numbering by leaf rather than by page – is “Sermo in festo praesentationis beatissimae Mariae virginis” by Arnold Ther Hoernen, published in Cologne in 1470.

Link: https://digital.ulb.hhu.de/urn/urn:nbn:de:hbz:061:1-96335

Direct link: https://digital.ulb.hhu.de/download/pdf/3381685.pdf

II. Why pagination took time to catch on

Although foliation – numbering leaves instead of pages – appeared as early as 1470, it took several decades for printed page numbers to become a common feature in books. This delay was due to several factors:

– Early numbering systems were meant for production, not readers. These markings helped bookbinders assemble pages in the correct order, rather than guiding readers through content.

– Books were rare and expensive, often owned only by institutions or wealthy individuals who used them for intensive study. Readers typically navigated texts by chapter or section headings rather than page numbers.

– The printing industry lacked standardization in its early decades. Each printer developed their own practices, leading to wide variation in layout, structure, and whether or how books were numbered.

Over time, as books became more affordable and accessible to a broader audience, the need for navigational tools grew. By the 16th century, pagination – numbering every page rather than each leaf – began to replace foliation, becoming a standard typographic convention.

Various examples: https://www.earlyprintedbooks.com/misc/pagination/

Roman numerals were traditionally used in early Latin books, most commonly in introductions, prologues, chapter titles, or section headings. However, as books grew in length and complexity, Arabic numerals gradually replaced them, becoming the standard for pagination. This transition was driven by practical reasons: Arabic numerals are easier to read, especially for higher page counts; they are more compact, take up less space in print; and they better serve the growing need for navigational help such as indices, footnotes, and cross-references.

III. Possible rules for page numbering

In photobooks, pagination remains a little more flexible. There are no strict rules regarding the placement or presence of page numbers. Designers often choose to omit them entirely, especially in projects where the visual flow is important. When included, the most common positions are the bottom outer corner or the bottom center of the page, chosen for their subtlety and balance within the layout.

Tips for photobook pagination:

– Consistent placement

Page numbers should appear in the same location on every page where they are used. Inconsistency can distract the reader and disrupt the flow of the book. Also, it is usually considered unprofessional.

– Readability and aesthetic integration

Pagination should be sized appropriately for the format of the photobook – large enough to be readable, yet subtle enough not to compete with the photographs. The typeface and size should complement the overall design. Avoid placing page numbers too close to the page edge or inside trim margins.

– Skip functional or front matter pages

Pages such as the title page, copyright page, dedication, acknowledgements, colophon, and sometimes even the table of contents, traditionally do not display a printed page number – even though they are still counted in the total pagination.

– Pagination and full-spreads

When a single photograph spans an entire spread as a full-bleed image (extending to the edge of the paper with no margins), pagination is typically omitted. Including page numbers in this case would interfere visually with the photograph. If the image spans the spread but does not bleed to the edges (maintaining margins), it is common practice to include a page number on only one side of the spread – usually in the bottom outer corner, ideally on the page where the image begins.

IV. When page numbers are omitted

In some photobooks, page numbers are intentionally left out – a decision often driven by the conceptual vision. This is especially common in artistic or conceptual photobooks, where pagination might disrupt the immersive experience, interrupt a cinematic narrative flow, or interfere with the desired rhythm and fragmentation of the visual sequence.

Omitting pagination can enhance the emotional or abstract qualities of a project, encouraging the reader to engage more intuitively. However, this approach is less common in documentary or archival photobooks, where page numbers are often essential for orientation, reference, or academic use. In such cases, the absence of pagination can hinder navigation and reduce clarity for the viewer.

Additional reading: “The Chicago Manual of Style – 17th Edition”

Link: https://archive.org/details/dokumen.pub_chicago-manual-of-style-17thnbsped/page/n19/mode/2up

Direct link: https://ia801506.us.archive.org/33/items/dokumen.pub_chicago-manual-of-style-17thnbsped/dokumen.pub_chicago-manual-of-style-17thnbsped.pdf

V. Automatic pagination in publishing software

Most modern publishing software – paid and free – offers built-in tools for automatically adding page numbers to a document. These features streamline the layout process by generating consistent pagination across all pages.

However, these settings can be customised to suit the needs of a specific project. Designers may choose to start numbering from a particular page, skip certain pages, or apply custom page logic to align with the book’s structure or concept.

While this flexibility is valuable, manual overrides and custom numbering can introduce errors – especially in longer or more complex photobooks. It’s important to review the final layout carefully, as inconsistencies in pagination may only become apparent during prepress or after printing, requiring time-consuming corrections or, in worst cases, leading to costly print mistakes.

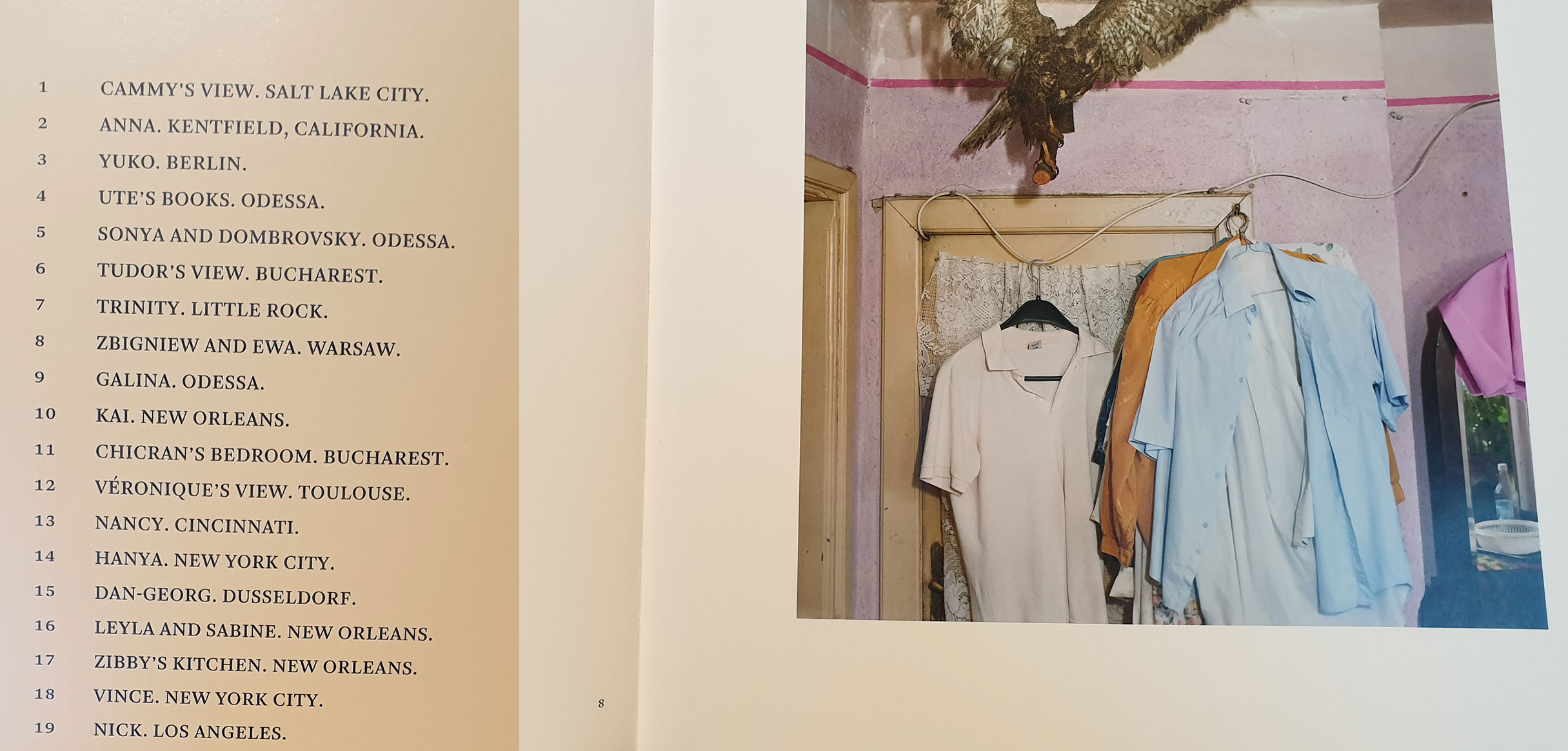

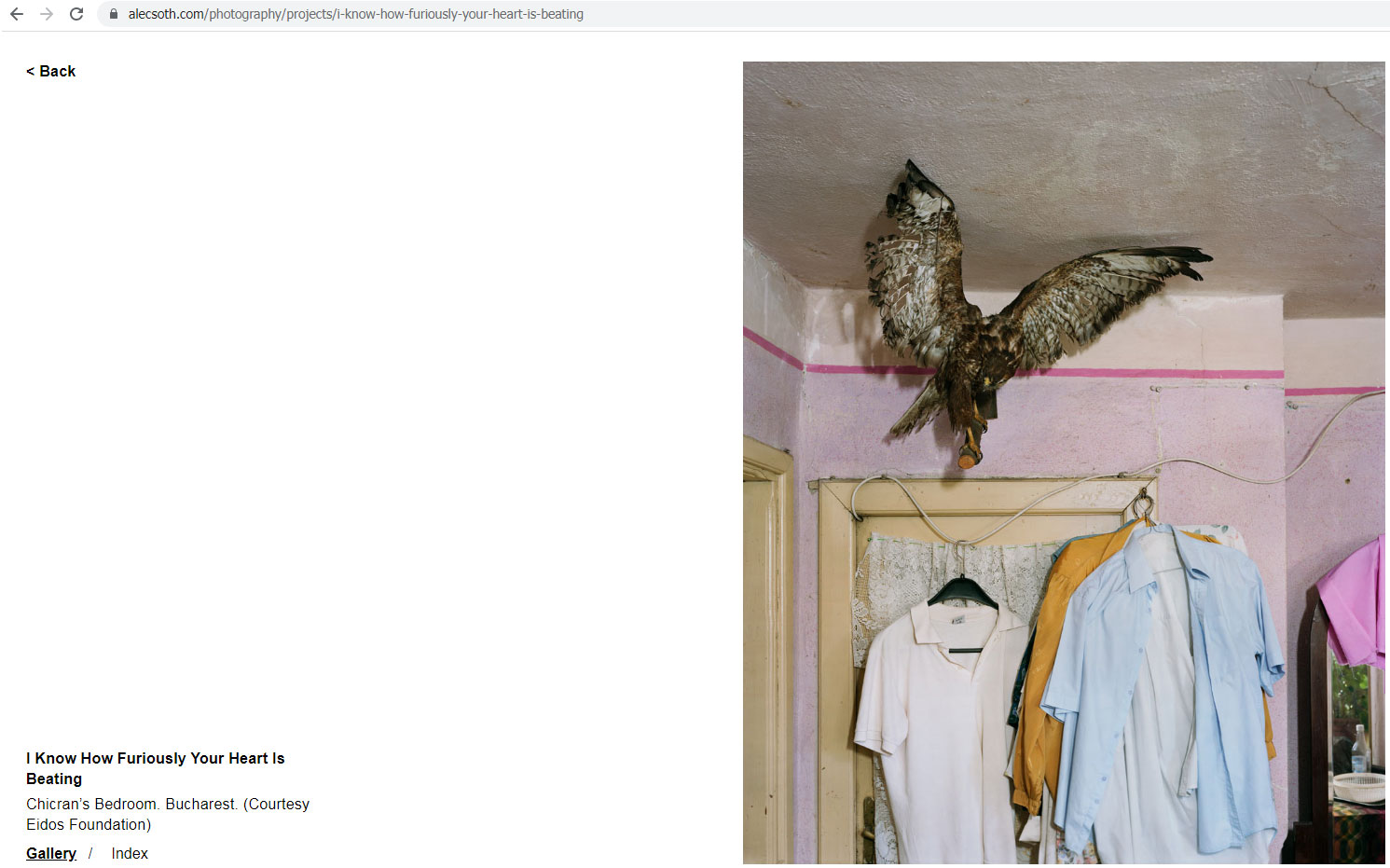

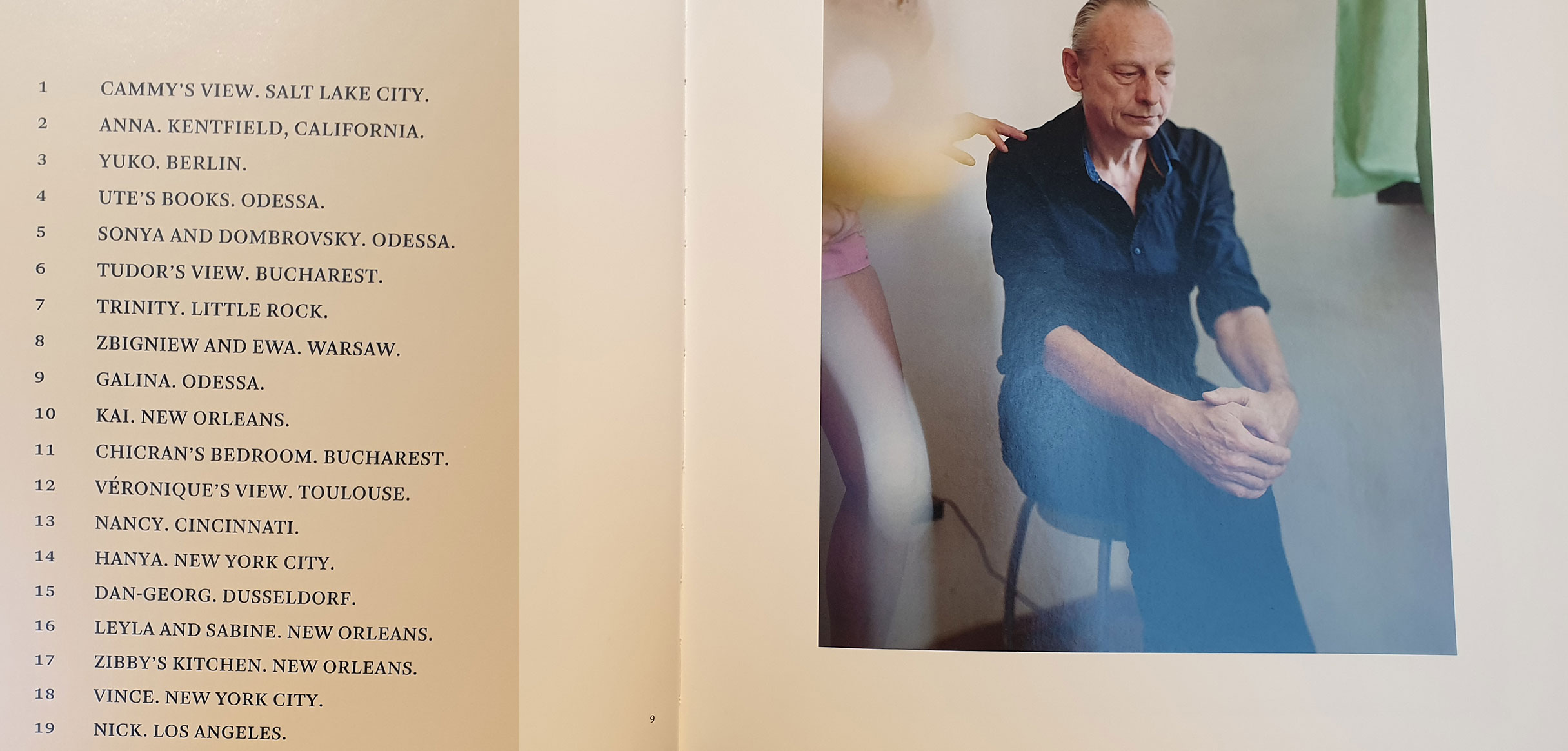

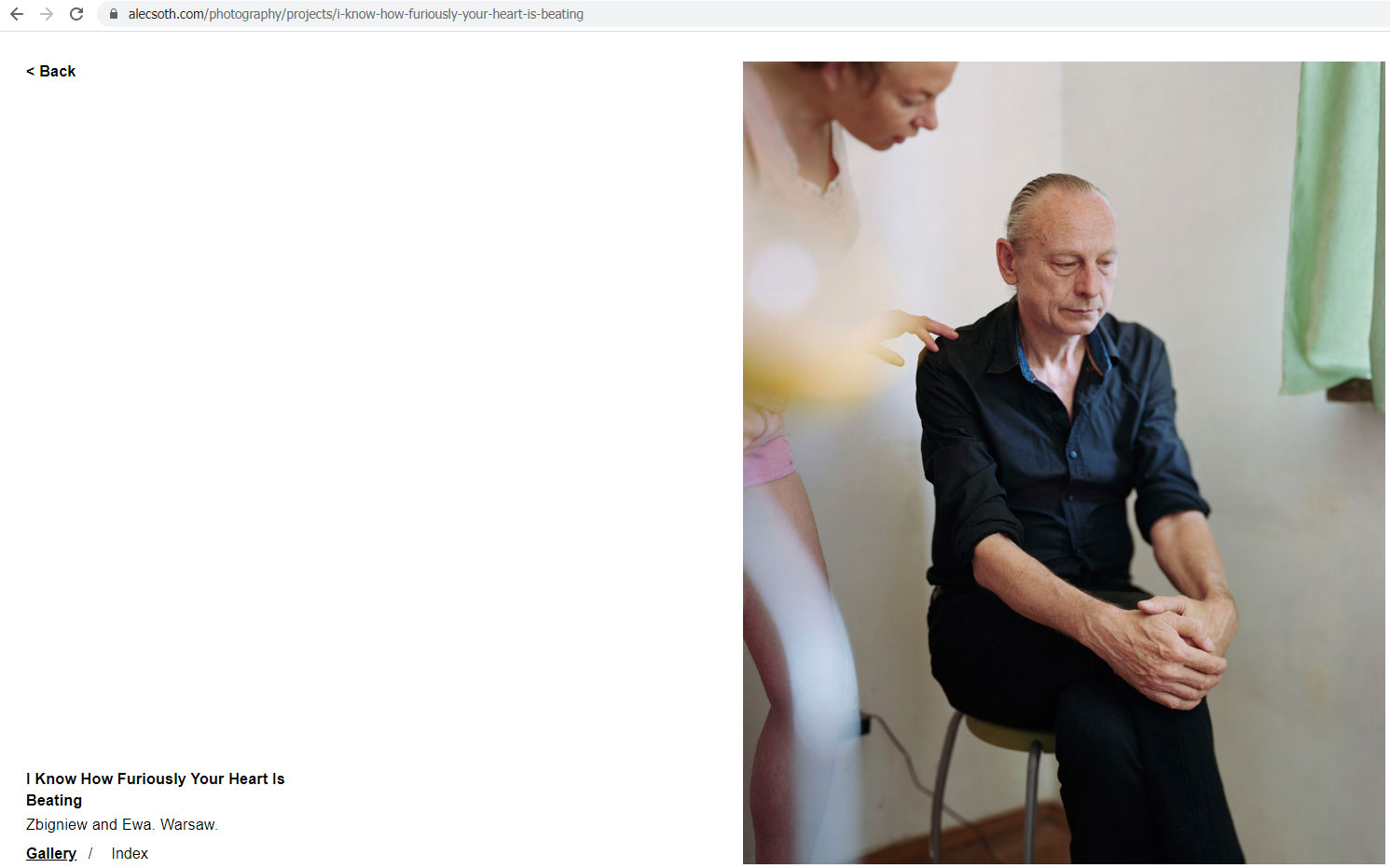

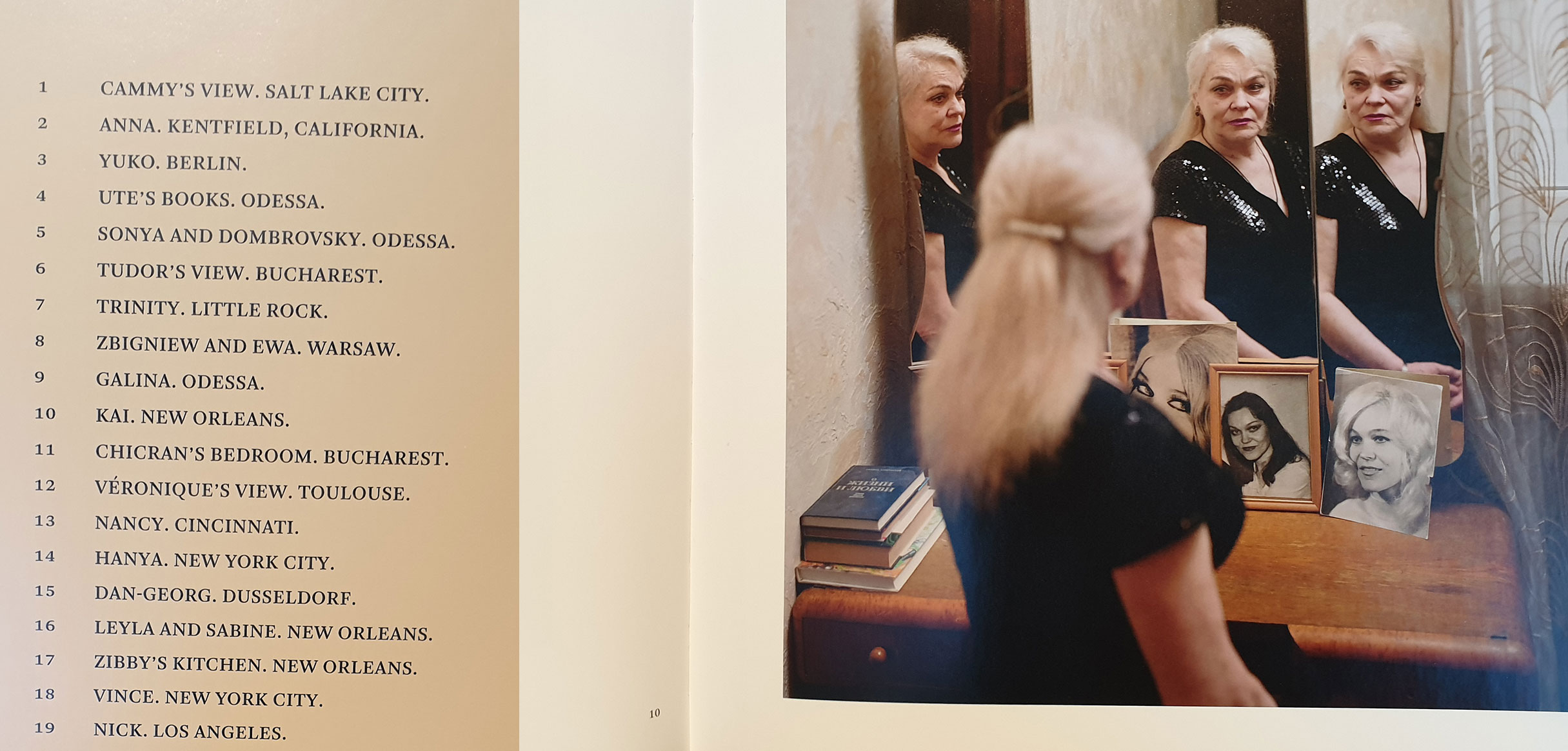

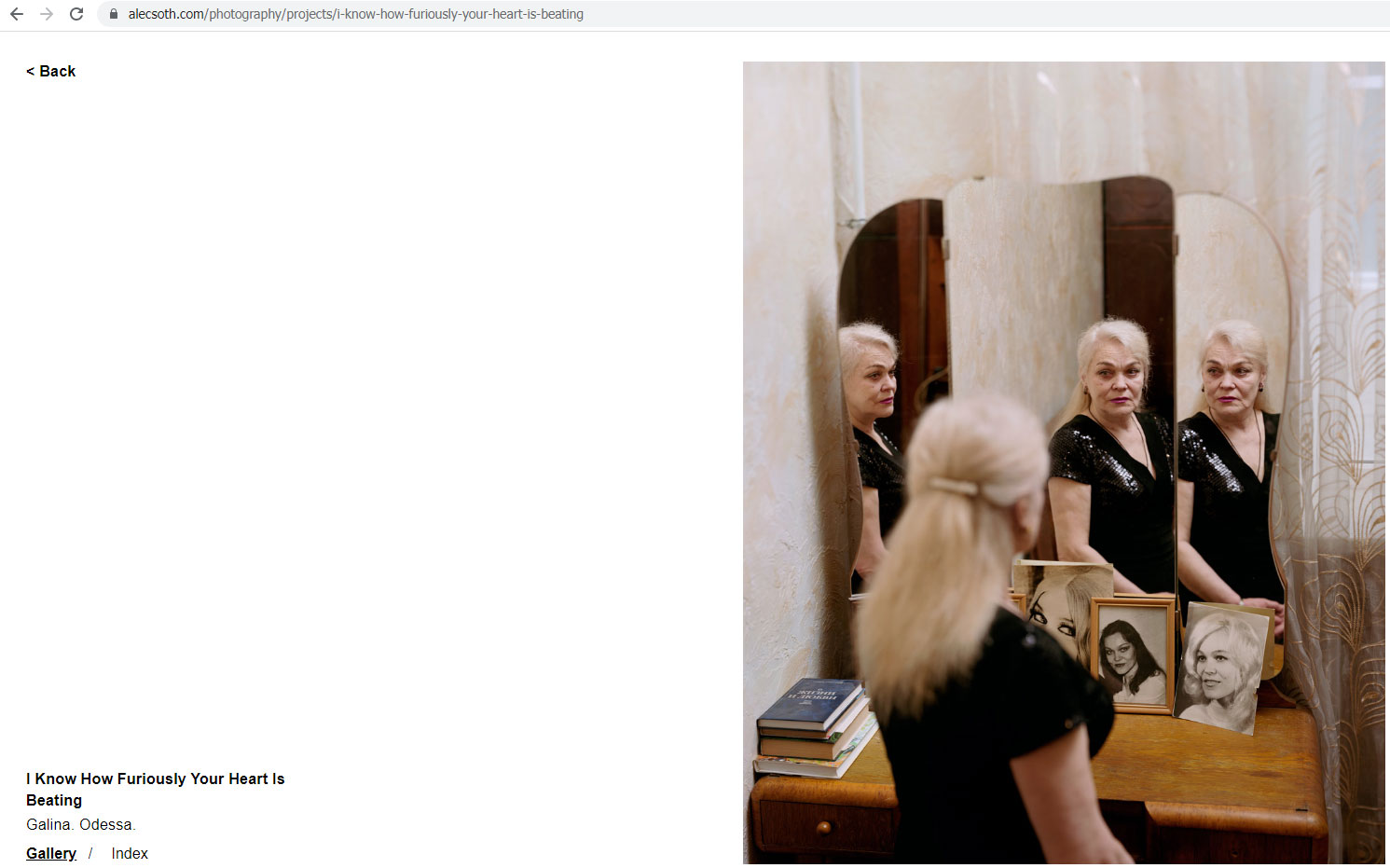

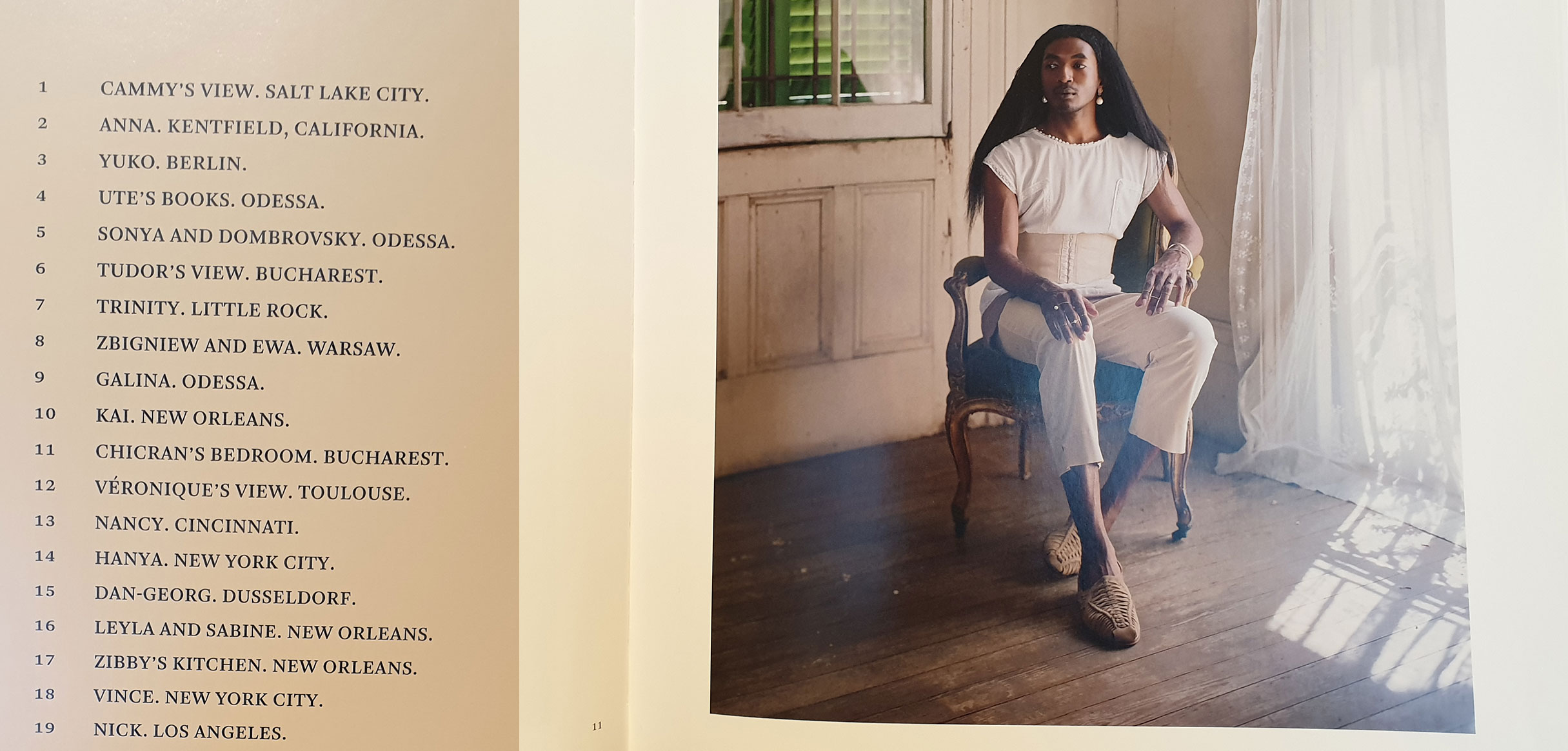

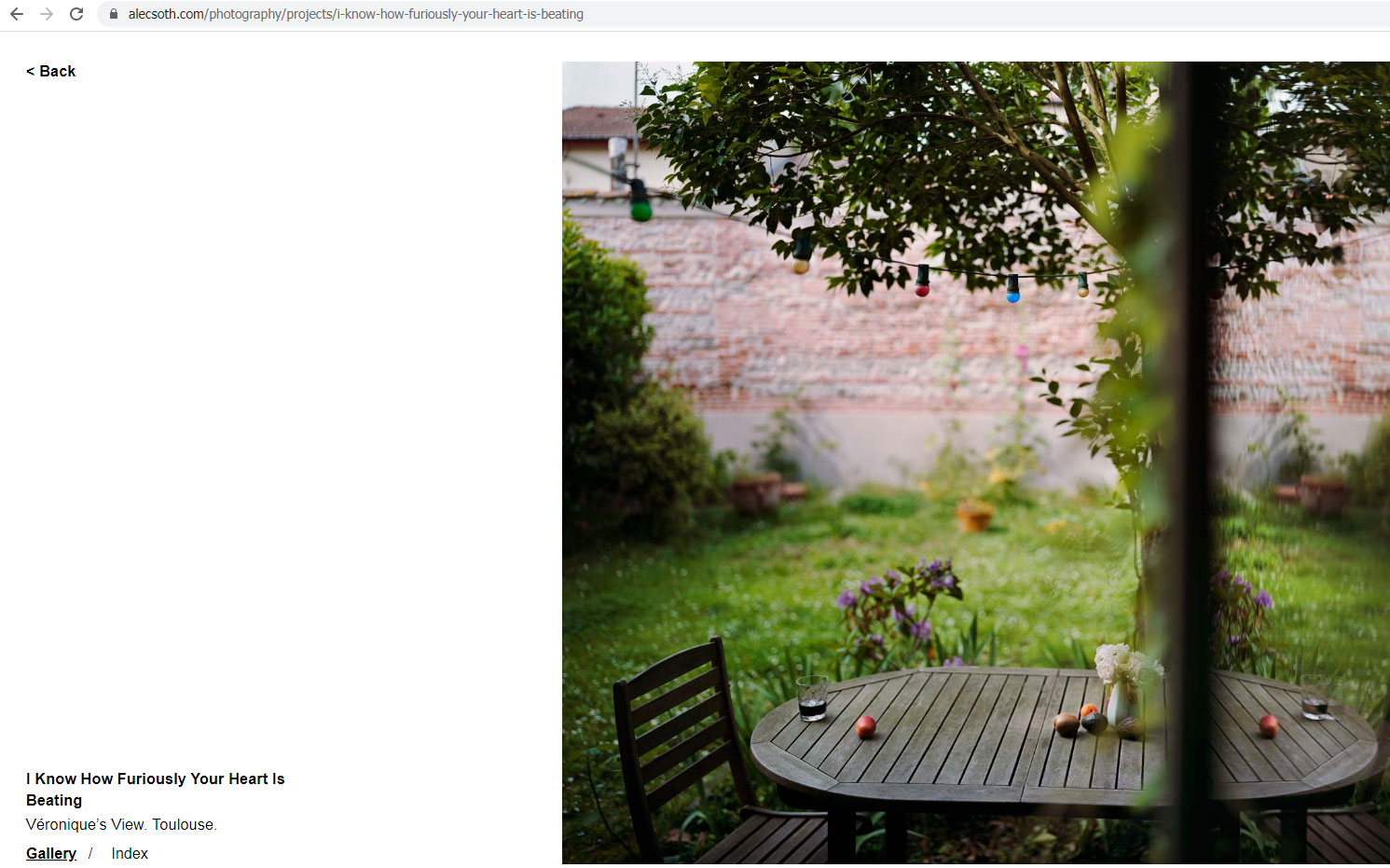

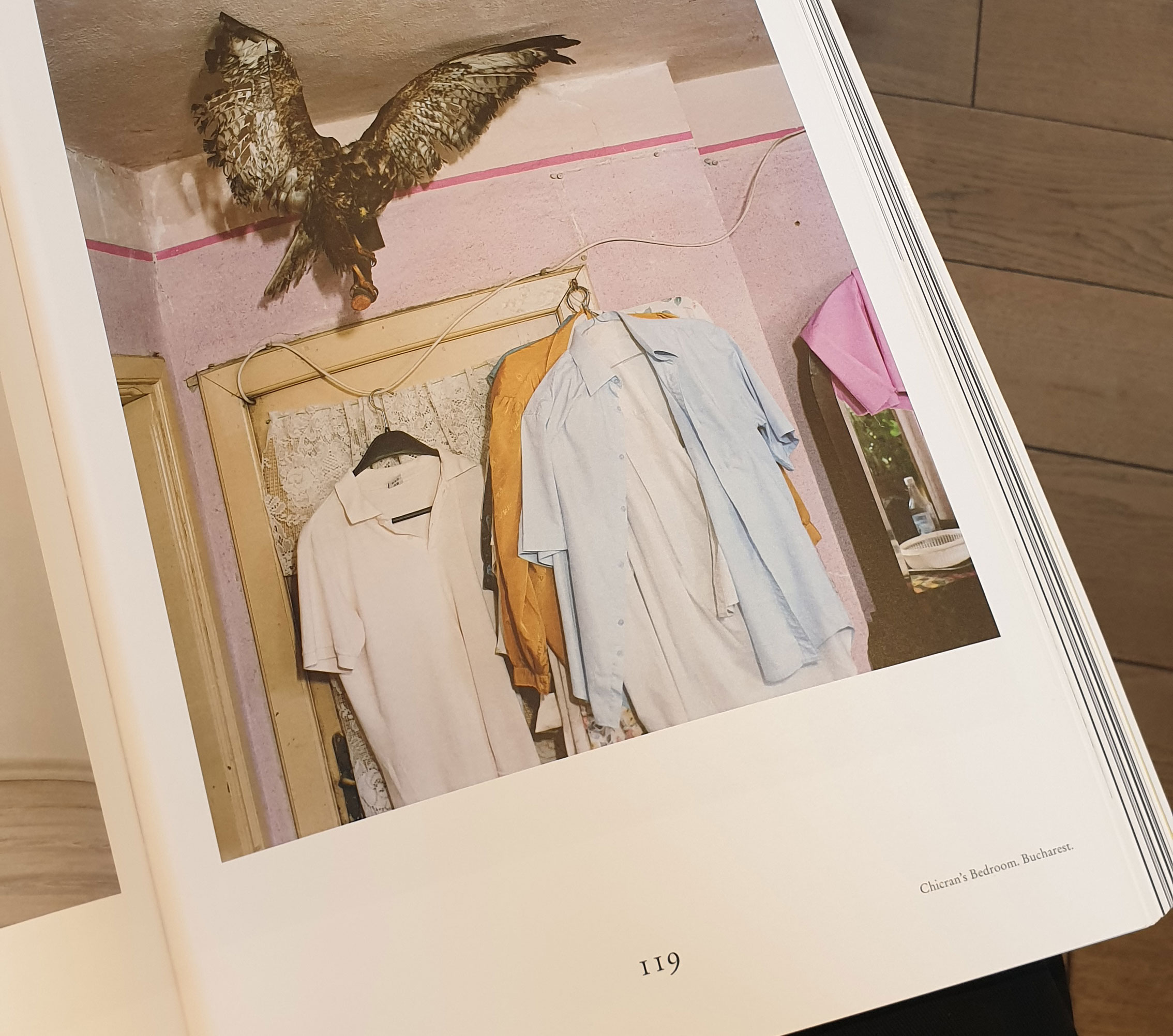

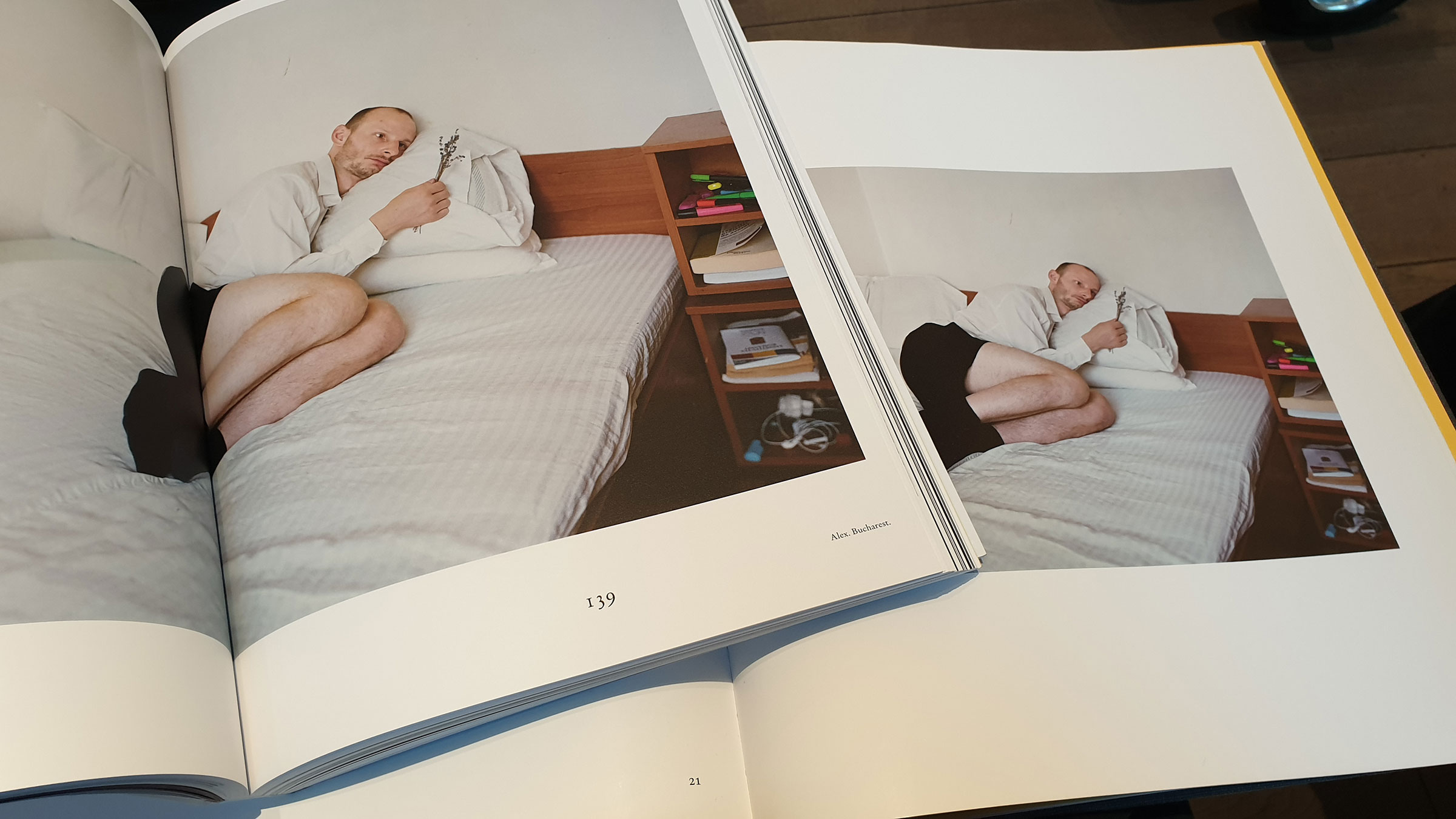

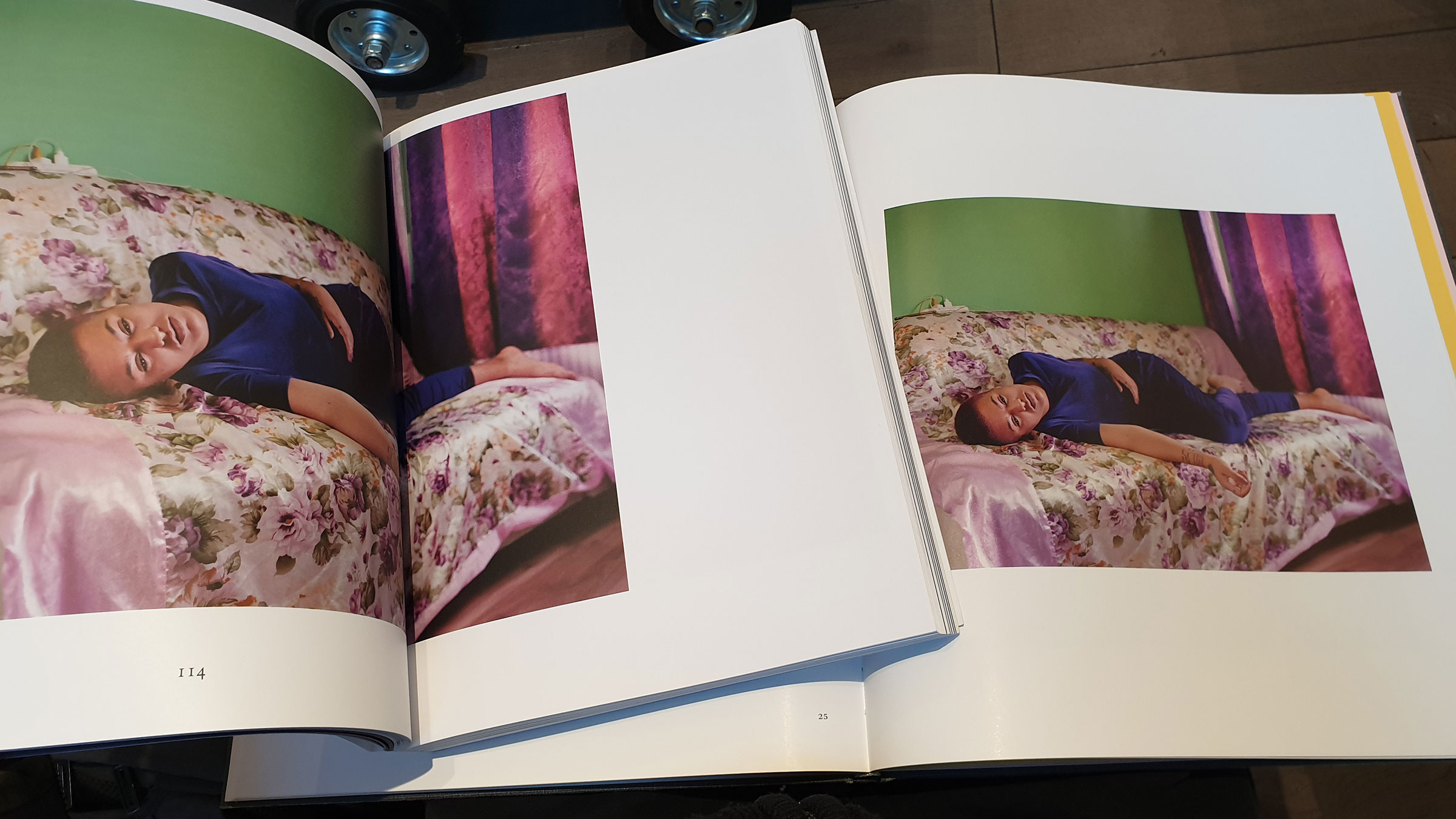

Below is an example from Alec Soth’s “I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating”: the left page is blank except for a page number positioned in the bottom inner corner near the spine, while the right page features a photograph. This layout suggests that the spread pairs a page number with a corresponding image, intended to align with the book’s table of contents.

However, there appears to be a pagination error in both the first and second printing of the photobook: a shift between the page numbers and the photographed subjects disrupts the intended sequence. It is likely that the author aimed for the numbering and image order to correspond exactly with the contents list, but a manual intervention on the page numbering has caused inconsistencies.

1st photo: Left – table of contents, right – spread from the photobook

2nd photo: screen capture from official websites

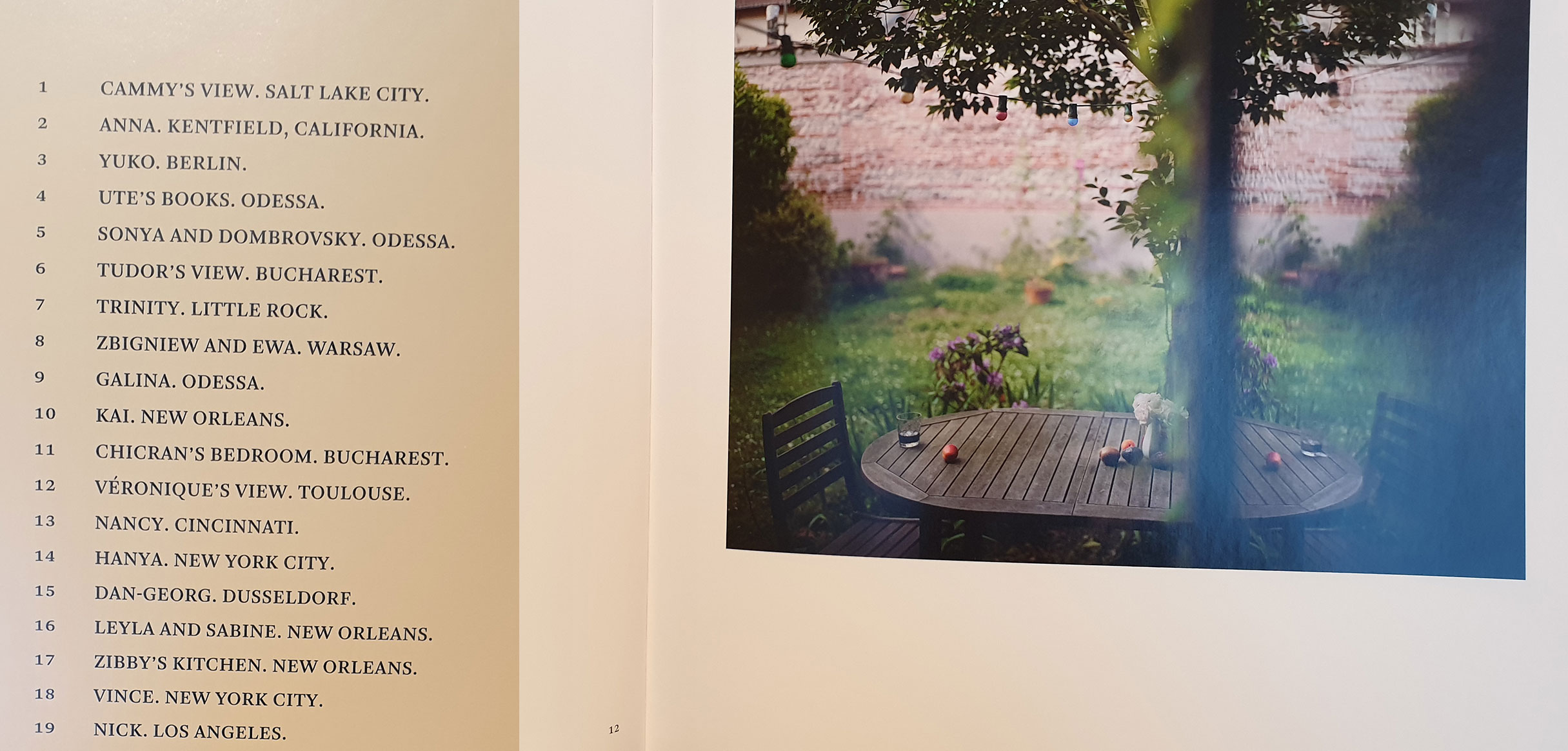

The correct page numbering starts again from page 12 and the shift between the page numbers and the photographed subjects is no longer present.

1st photo: Left – table of contents, right – spread from the photobook

2nd photo: screen capture from official websites

Sources:

Book: https://mackbooks.co.uk/products/i-know-how-furiously-your-heart-is-beating-second-printing-br-alec-soth

Project: https://alecsoth.com/photography/projects/i-know-how-furiously-your-heart-is-beating

Project: https://www.magnumphotos.com/theory-and-practice/alec-soth-cleansing-the-visual-palate/

Contents page: https://mackbooks.co.uk/cdn/shop/products/Alec_Soth28_e77d5cec-004e-42d7-9cdd-218114c2a966.jpg

Page 10: https://mackbooks.co.uk/cdn/shop/products/Alec_Soth9_a56fd9f1-ee6a-4211-822d-fc0fa7576a35.jpg

Page 11: https://www.photobookstore.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Alec-Soth-I-Know-How-Furiously-Your-Heart-is-Beating9.jpg

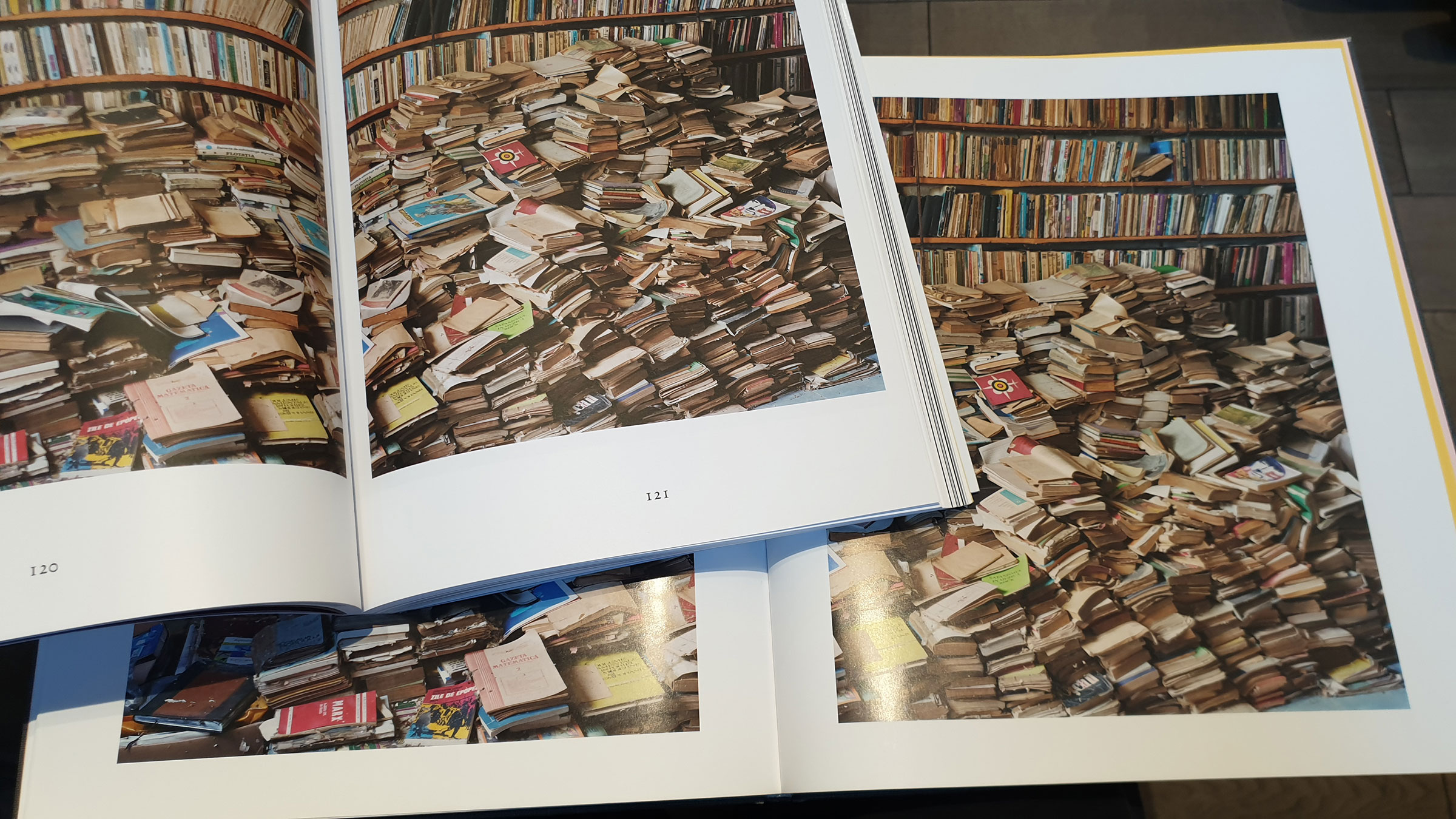

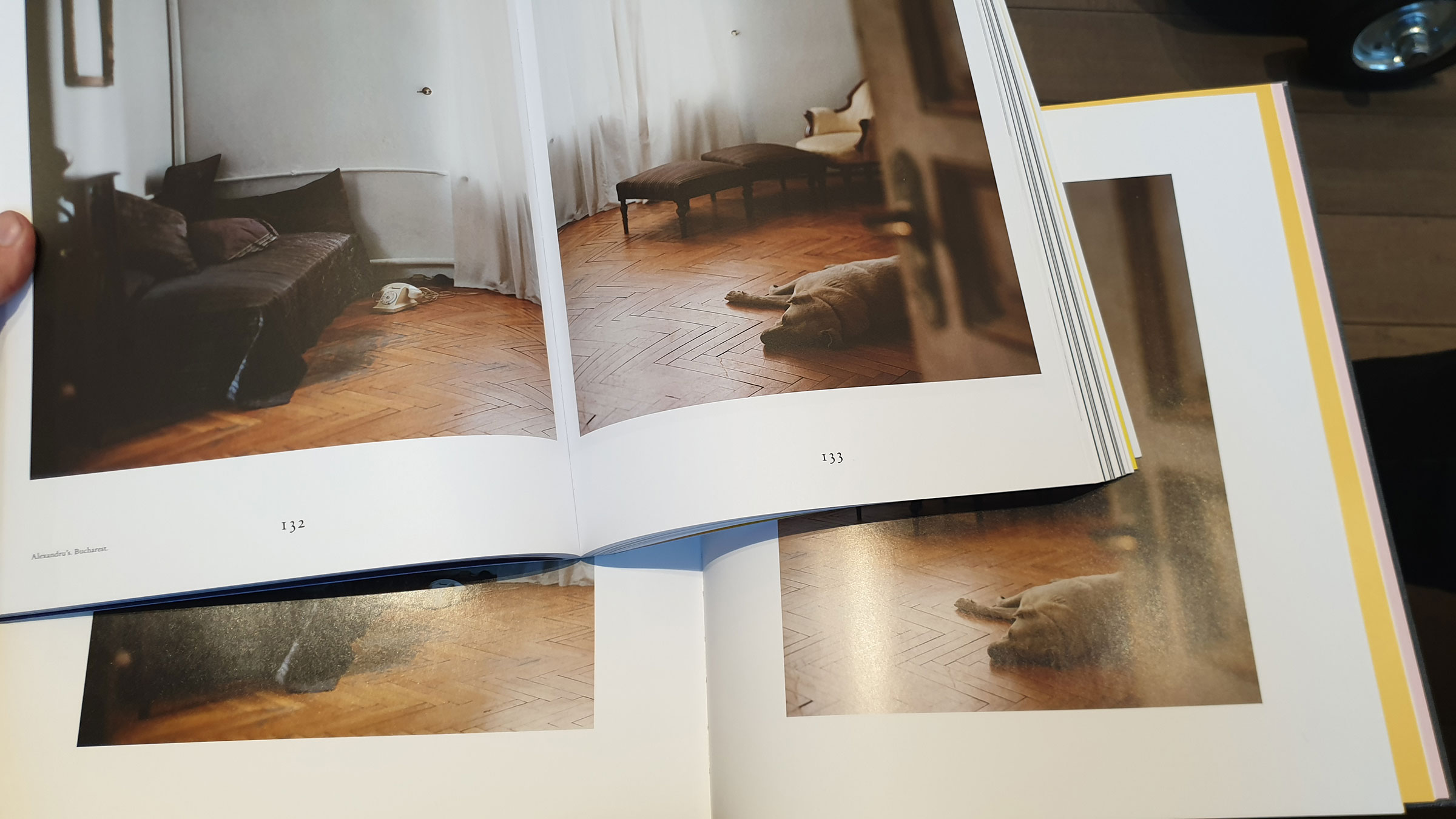

In another photobook titled “Romanias”, many of the photos from “I Know How Furiously …” are included, but this time both the page number and the caption appear on the same page as the image/spread. This represents a different design choice – one that simplifies the structure and reduces the likelihood of pagination or sequencing errors.

top photobook: “Romanias”

bottom photobook: ‘I Know How Furiously …”

Sources:

Book: https://www.eidosfoundation.org/romanias/

Project: https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/society/six-photographic-visions-contemporary-romania-photography-exhibition-book/

VI. The last page

From its origins as a practical aid for bookbinders in the 15th century, pagination has reshaped how we navigate books. The gradual shift from leaf numbering (foliation) to page numbering (pagination), and the widespread adoption of efficient Arabic numerals, transformed books from rare, intensely studied objects into accessible tools for broad knowledge sharing and easy referencing.

In photobooks, this evolution introduces a unique flexibility. While navigation remains important, the visual narrative often takes precedence. Designers and editors frequently make a conscious choice: to subtly include page numbers for orientation, or to omit them entirely to preserve the immersive flow of full-bleed images. Ultimately, pagination in a photobook is more than just a number; it’s a deliberate design decision that balances function with artistic expression, guiding the viewer through the visual story in a carefully considered way.